The model of play state[1] is a designer’s answer to the question of what play sate is from the player[2]’s perspective, that is, what exactly the essence of play, the “power of maddening” lies in.

Most of them [the explanations] only deal incidentally with the question of what play is in itself and what it means for the player. They attack play direct with the quantitative methods of experimental science without first paying attention to its profoundly aesthetic quality. As a rule, they leave the primary quality of play as such, virtually untouched. To each and every one of the above “explanations” it might well be objected: “So far so good, but what actually is the fun of playing? Why does the baby crow with pleasure? Why does the gambler lose himself in his passion? Why is a huge crowd roused to frenzy by a football match?” This intensity of, and absorption in, play finds no explanation in biological analysis. Yet in this intensity, this absorption, this power of maddening, lies the very essence, the primordial quality of play. (Huizinga, 1949, p.2)

Veronika Szalai: The model of play state / DLA (Doctor of Liberal Arts) research / supervisors: Pál Koós, professor; Anikó Illés, PhD habil., associate professor // artist: Veronika Szalai / materials of object: copper, iron, neodymium magnet / / media artists: Csanád Szesztay, Bea Pántya / puppet artist: Borbála Egri / date: MOME (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) DLA 2023

Doctoral dissertation: Play-based activities – The player’s perspective of play state

Masterwork: The model of play state – Abstract dynamic fields of play

[1] The abstract field in the player’s consciousness where the player’s actions take place.

[2] Ego, self

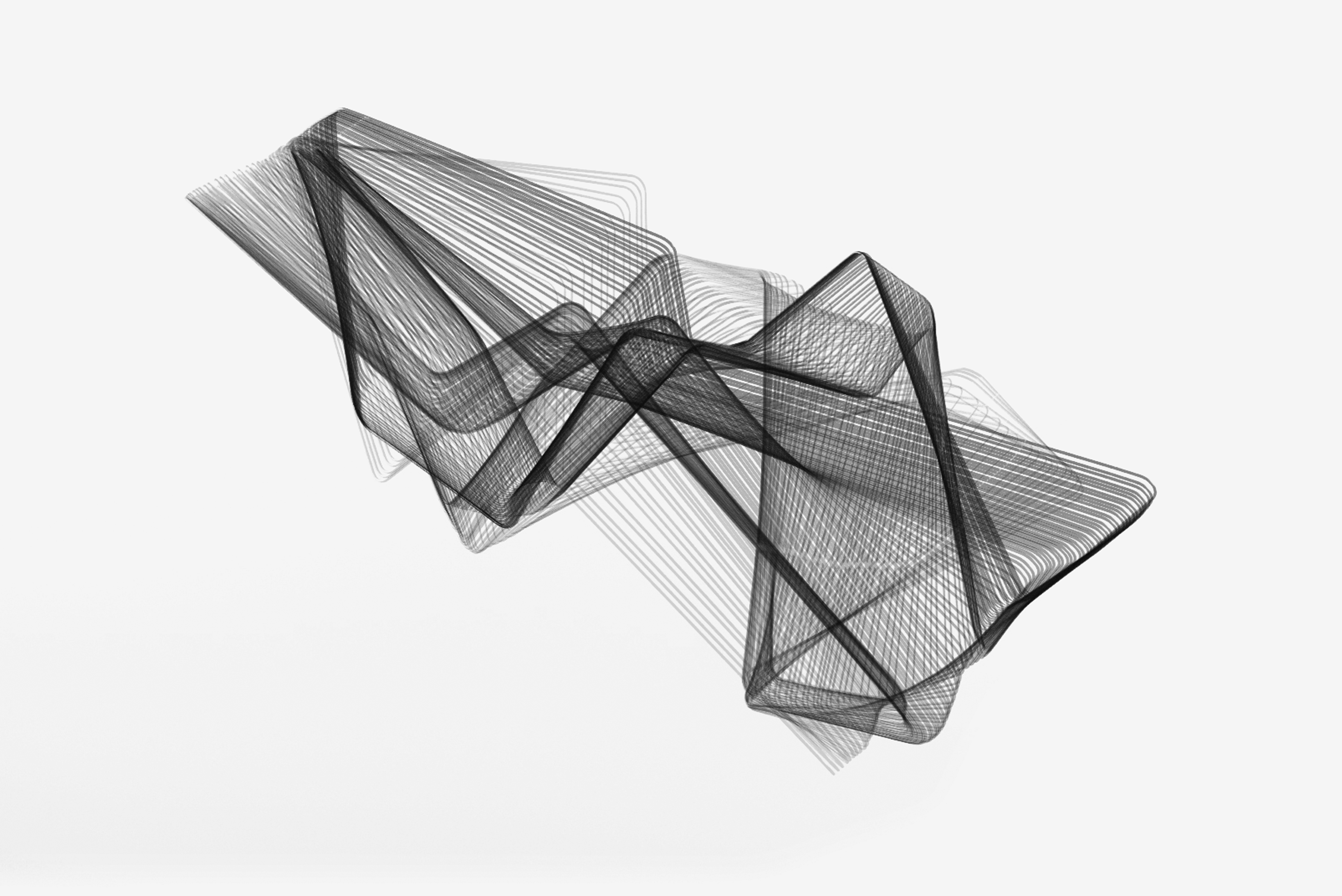

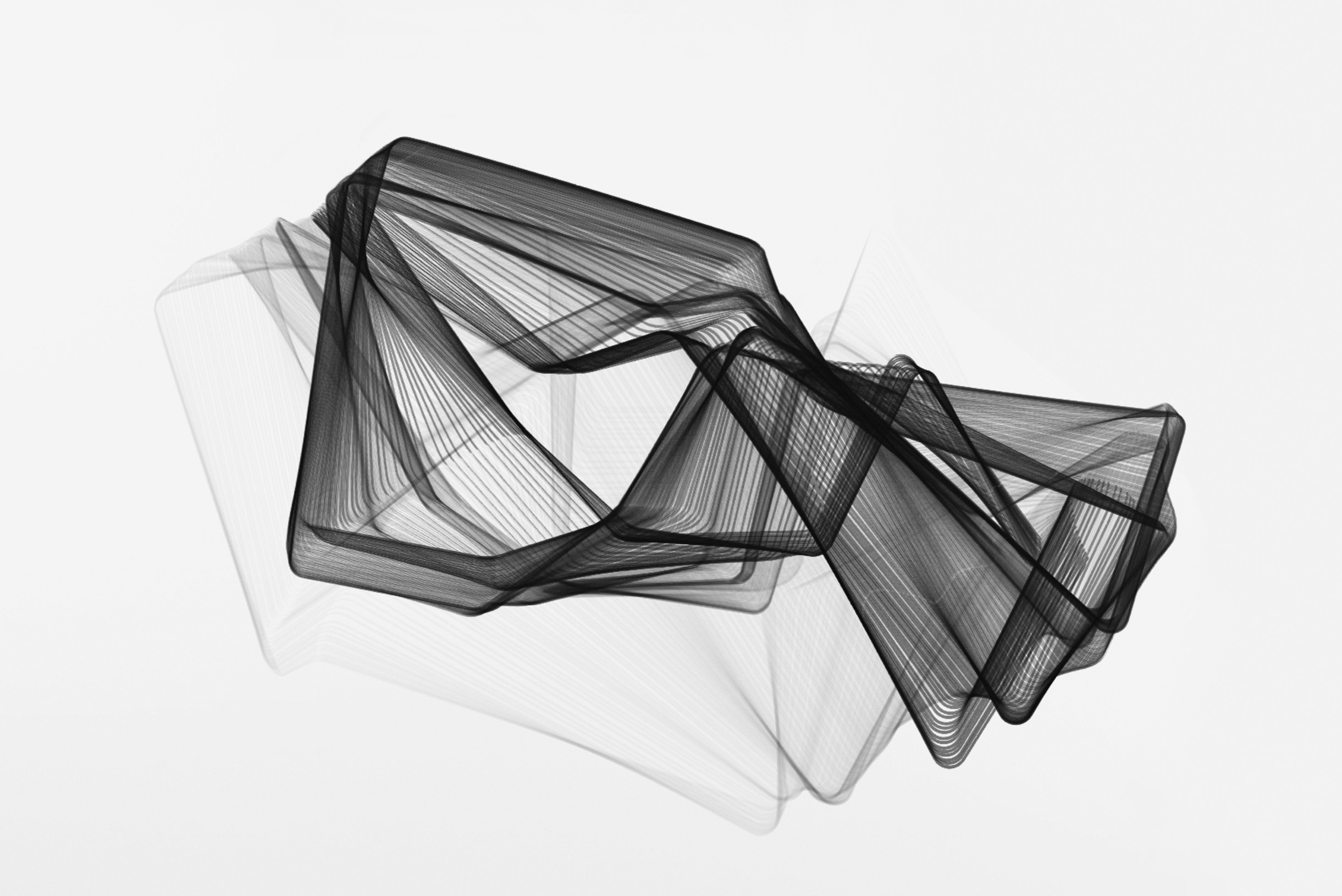

Some trajectories of the model of play state, 2023, artist: Veronika Szalai,video: Csanád Szesztay, Bea Pántya

We all have our own distinctive perceptions of play, which makes it quite a challenge to answer the above question. Disregarding infants, there are some 8 billion different, individual perceptions. To further complicate matters, this number multiplies immensely when one is in play state, since then the static image in people’s minds, all of a sudden, becomes a dynamic and ever changing one.

Doing some research, one may find definitions of play that quite contradict each other, reflecting the different approaches prevalent in different ages. However, it is essential how we approach play as it is an activity that, ideally, is characterised by the fact that it is self-imposed and done for its own sake. Consequently, it must have an inner, “psychological common currency” (Fredrickson et al., 2009, p. 363), providing players with positive reinforcement that makes them take risk and venture into the realm of play based activities, over and over again. All activities that provide the player with a sense of being in play state may be considered play based activities from the player’s point of view. When I hear screams and thumps and desperately dash into the children’s room only to find out that my giggling daughters are practising nose diving, it is self-evident that I am not the one who is in play state.

The model of play state, 2023, artist: Veronika Szalai, video: Csanád Szesztay, Bea Pántya, puppet artist: Borbála Egri

Let us have a closer look at what this common currency, this power of maddening really is. It is none other than the aesthetic experience of play state, which fundamentally consists of the player’s emotions. These emotions provide meaningful feedback of the activity only to the players and make them continue their actions. During play the aesthetic experience of play state may be grasped, as the player’s emotions form a well-defined network, an open and formable, still solid structure that moves freely and allows the player to experience its elements in different ways and orders. It is akin to music played by an orchestra: one may break down the whole into music played by each individual musician, woven together by the conductor into one piece by controlling the dynamics of when each instrument enters and stops playing.

When designing a game or play based activity we may assign external, easy to represent secondary reinforcers (awards, points, likes, medals, etc.) to this intricate system so that we could influence or limit the number and direction of the player’s actions. This way we may create game structures that vary greatly in quality: some may inspire and empower the players, while others may manipulate them and make them obsessed.

Besides it being a dynamic emotional system, there are indeed some specific qualities of the aforementioned 8 billion individual perceptions that may well be considered universal traits of human play. The interesting thing about these qualities is that by means of conceptual-logical thinking they may be arranged in pairs of antonyms, such as open-closed, constant-changeable, clear-blurred, stable-instable, limited-free, controlled-uncontrolled, random-systematic etc., but in visual representation these concepts mutually presuppose each other. If we depict these universal concepts of play state in a unified system, these numerous individual perspectives become easier to compare and allow us to have a critical approach to the game structures we design.

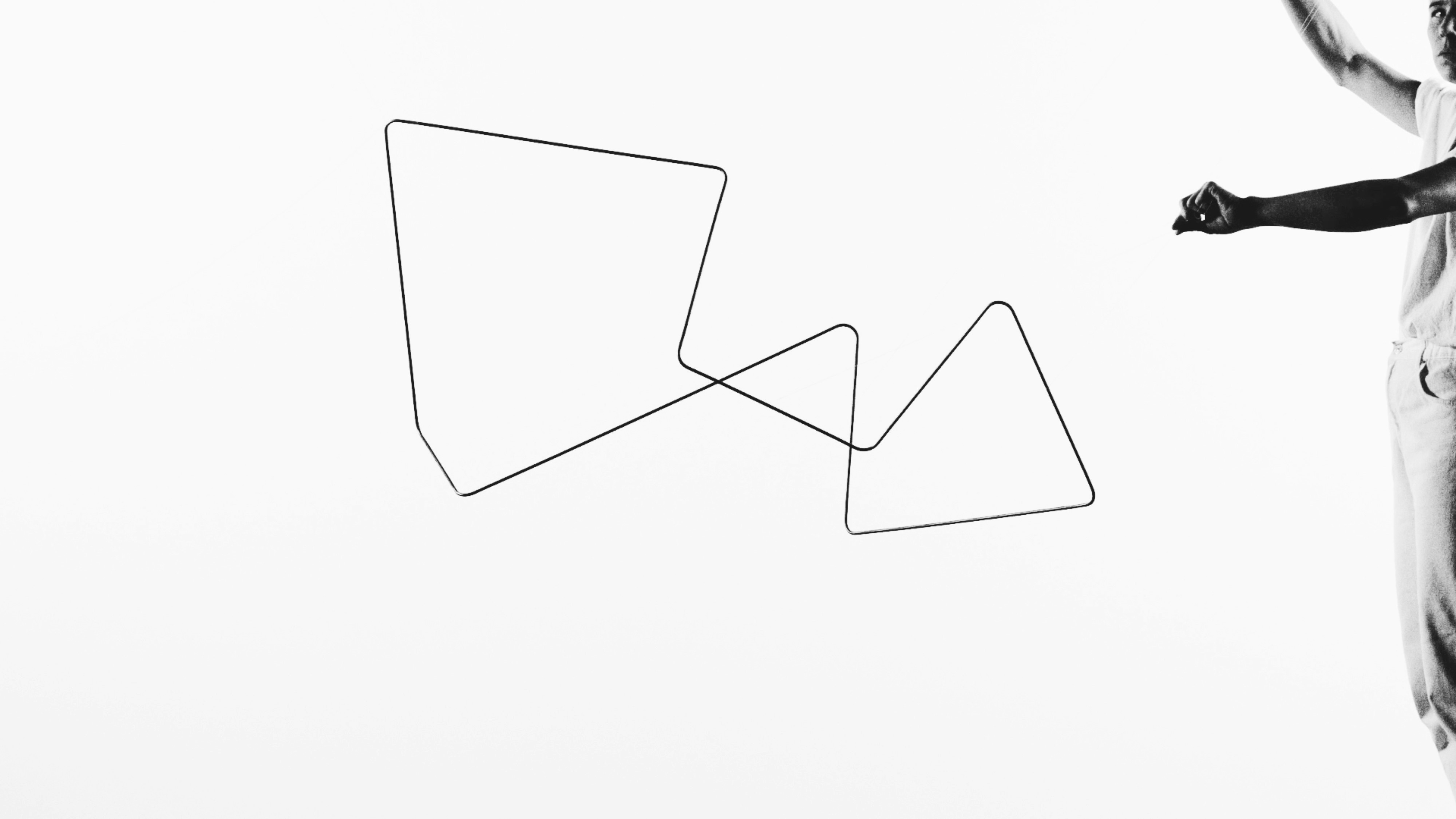

My artwork displays the universal aesthetic experience of play state by means of a physical object, making the previously discussed intricate emotional system visible. By creating my artwork, I aimed at opening a designer’s perspective that allows for creating the outline of a supposed dynamic emotional and motivational system in the case of any game. In other words, creating the outline of the possible scenarios and the foundations of the supposed aesthetic experience of each game.

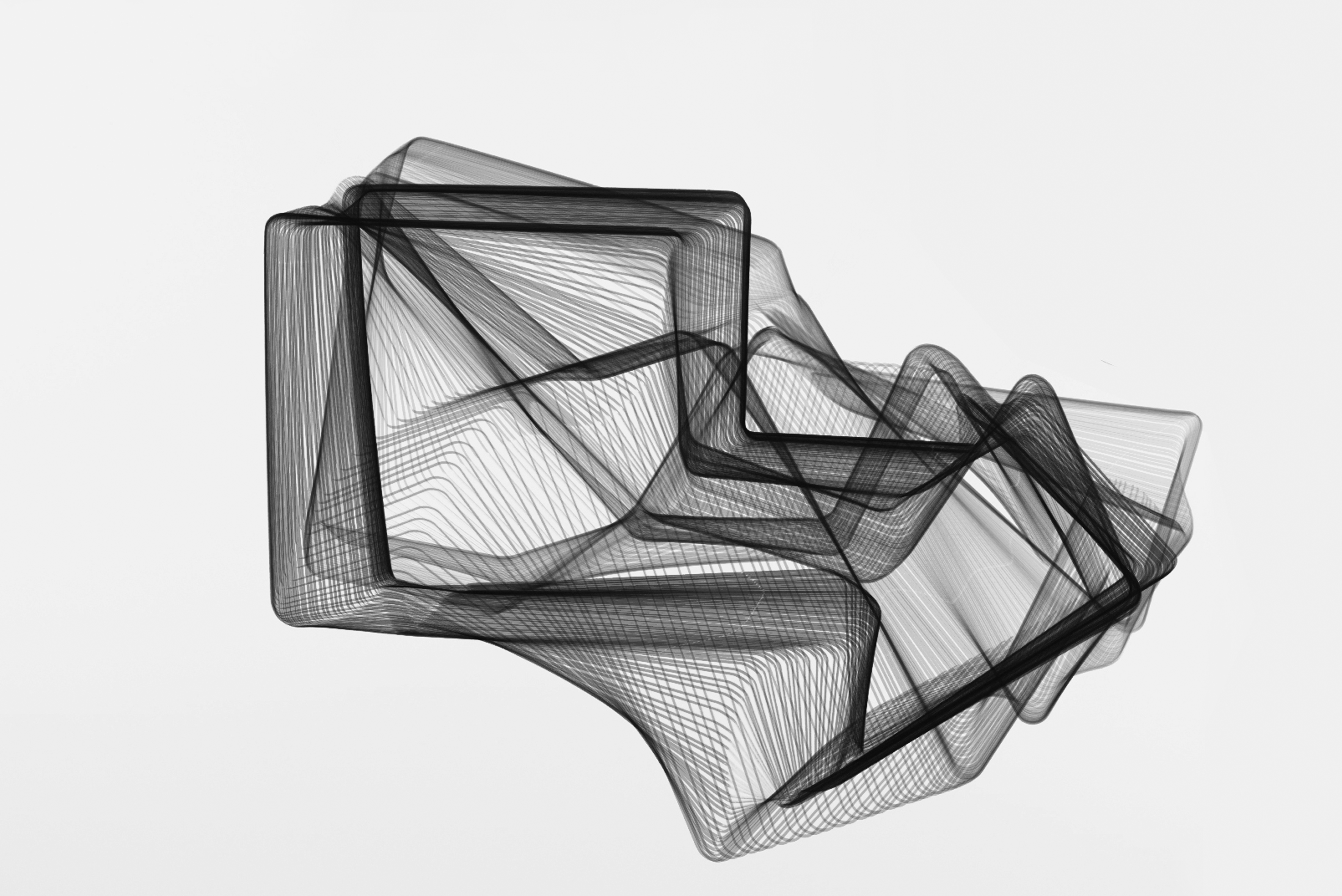

The elements and some trajectories of the model of play state, 2023, artist:Veronika Szalai, photo: László Szűcs, Csanád Szesztay

The artwork in contemporary cultural context

The artwork may be composed in numerous different ways using the provided set of physical elements. These elements make it possible to build and experience systems of different qualities: the builder may create a rigid and immovable structure of lines or one that allows for an opportunity for a lot of free movement. Thanks to the use of the inflexible material and the nodes that allow for free movement, by moving the object one may draw an everchanging abstract field of play.

In form my Masterwork is in line with the concept stressing the importance of negative space and trajectory in space formation prevalent in the 20th and 21st century sculpture. (Chau, 2017 and Weibel, 2021) In critical and experimental approach it is akin to Ludic Conceptualism in which Huizinga’s cultural theory of play served as a critical example for artists when they created their playful experiments. (Schoenberger, 2017) Ludic Conceptualism describes a genre that emerged in The Netherlands between 1959 and 1975 when ludic art of the period, used as a strategy for social criticism, overlapped with the conceptual art movement. In this period Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element of Culture served as an intellectual point of reference for those creating works of art, and the play element in these works was apparent.

For example, the exhibition titled Bewogen Beweging (Moving Movement) featured nearly two hundred works by over seventy artists from the United States and Europe, all of whom contributed art that either moved or addressed movement, constituting a survey of Kinetic art. It provided museumgoers with the novel spectacle of rusty wheels, chains, broken typewriters, strollers, and alarm clocks that moved and made noises. Bewogen Beweging was a ludic exhibition that served as a forum in which to question an indiscriminate embrace of machines. The artists’ playful critique incorporated illogical movements of mechanical components, demonstrating that play could be a serious response to and a questioning of the rapid industrialization and modernization in the Netherlands after World War II. Tinguely’s sculpture titled Cyclograveur, an anti-machine resembling a bicycle, was among the exhibits. This work was constructed from rusty parts scavenged from bicycles, cars, and baby carriages. The saddle was attached to a seat post twice the hight of a typical bicycle’s, while the pedals were connected to several gears and four wheels. A large drawing board was positioned about a meter beyond the pedals. When a participant climbed on the bicycle to push the pedals, a hidden cogwheel started moving an arm that drew on the drawing board. A bookstand in front of the handlebar allowed the “player” to read while pedalling, distracting the visitor from the creative process of drawing and letting the machine make the artistic “decisions”; the participant was needed only to power the machine. The main criticism the exhibition attracted was that due to its entertaining nature, and because of the personal experience of the visitors, it concealed its real message, the social critique. (Schoenberger, 2017)

The model of play state, 2023, artist: Veronika Szalai, video: Csanád Szesztay, Bea Pántya, puppet artist: Borbála Egri

In our age of gamification (Jagoda, 2020) designed game structures appear in all areas of life. The quality of these structures varies greatly: some may inspire and empower certain players, while others may manipulate them and make them obsessed. This quality, among other things, depends heavily on the number of movements, that is, the number of interactions between the player and the abstract field of play. Given the fact that game structures are designed features, one cannot avoid reflecting on the responsibility of the designer.

My Masterwork is an attempt at demonstrating the designer’s responsibility. I created an autonomous work of art, a physical object, which proves that by using the same set of elements one may design structures of any quality, from totally rigid and immovable ones to systems that only support a few interactions to those that provide an opportunity for an infinite number of movements.

On an abstract level, the set of elements of play state mainly consists of the player’s emotions which form a network. While the interrelationship of these elements within the network is stable, it also moves freely and allows the player to experience the elements in different ways and orders. The essence, the aesthetic experience of a quality play state is none other than the coordinated but diverse movements of these emotional elements.

In my Masterwork the abstract field of play consists of physical nodes and links between them. My artwork focuses on a quality play state and provides the player with an open and formable, still solid structure, and the opportunity for an infinite number of free, repeatable movements within it, exemplifying that the responsibility of the designer in creating the framework of play is greater than one might think.

However, considering Huizinga’s cultural context and the message of Ludic Conceptualism, we can conclude that the responsibility does not only lie with the designer, rather it is a collective cultural responsibility. Both the incentive values created by a designer and the secondary reinforcers created by cultural effects, such as money or good grades, are capable of interfering with the primary reinforcement of the “player” in a way that it may not serve the survival of the individual or that of humankind. Thus, every one of us has an ultimate responsibility, and also a great potential, to shape the cultural framework we all share.

The elements and a composition of the model of play state, 2023, artist: Veronika Szalai, photo: László Szűcs, Csanád Szesztay, puppet artist: Borbála Egri

References

Huizinga, J. (1949). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element of Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fredrickson, B. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Loftus, G. R., & Wagenaar, W. A. (2009). Atkinson & Hilgard’s Introduction to Psychology. Andover: Cengage Learning.

Chau, C. (2017). Movement, Time, Technology, and Art. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Weibel, P. (2021). Negative Space: Trajectories of Sculpture in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schoenberger, T. J. (2017). Ludic Conceptualism: Art and Play in the Netherlands, 1959 to 1975. New York: CUNY Academic Works.

Jagoda, P. (2020). Experimental Games: Critique, Play, and Design in the Age of Gamification. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.